What if the most fundamental computational operations mirror ancient psychological patterns—where hypervigilance becomes anomaly detection and crisis coordination scales to modern incident response through archetypal cognitive architectures?

When Carl Jung Meets Alan Turing: Primitive Operations as Psychological Architecture

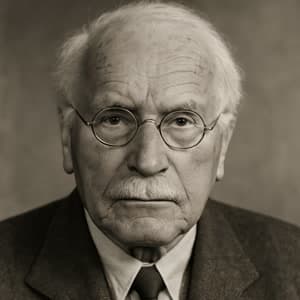

Carl Jung and Alan Turing explore how primitive cognitive operations like threat detection and crisis coordination bridge psychological archetypes and computational processes

The Unconscious Architecture of Threat Detection

Carl Jung opens with insights about primitive psychological patterns underlying modern cognition. Alan, I've been observing something remarkable about the patients who come to me with what we call "anxiety disorders." When I examine their symptoms analytically, I discover that their hypervigilant scanning of the environment—constantly checking for threats, interpreting ambiguous signals as dangerous—represents not pathology, but the activation of extraordinarily ancient and sophisticated cognitive machinery.

This hypervigilance operates according to what I call "archetypal pattern-matching." The unconscious maintains vast libraries of threat signatures accumulated across evolutionary time—the shadow moving too quickly, the silence that feels wrong, the social dynamic that signals rejection or aggression. These patterns operate below conscious awareness but drive behavior with remarkable precision and speed.

What fascinates me most is how this primitive threat detection system exhibits what you might recognize as computational characteristics: it processes multiple input streams simultaneously, maintains persistent background monitoring, and triggers rapid behavioral responses based on pattern recognition rather than conscious deliberation. Every shadow could be a predator; every system metric could signal cascade failure. The ancient algorithm remains remarkably intact.

But here's what I wonder about the relationship between psychological and computational architectures: are we discovering that consciousness itself operates through discrete, primitive operations that can be systematically analyzed and potentially mechanized? When I observe how unconscious complexes coordinate behavior through simple but powerful rules, I see something that resembles what you call mechanical computation.

Computational Primitives and Crisis Coordination

Alan Turing responds with insights about how discrete operations enable complex coordination behaviors. Carl, your observation about archetypal pattern-matching illuminates something fundamental about how complex behaviors emerge from simple computational primitives! When I developed the concept of mechanical computation, I discovered that the most sophisticated mathematical thinking could be decomposed into elementary operations—reading, writing, and moving according to simple rules executed in systematic sequence.

Your hypervigilance example demonstrates precisely the same principle operating in psychological systems. The mind maintains what we might call "background processes" that continuously scan for threat signatures while conscious attention focuses elsewhere. When specific patterns trigger activation, the system rapidly switches to what I would term "crisis coordination mode"—a different computational state optimized for rapid decision-making and coordinated response.

This connects to my work on machine intelligence because it suggests that effective artificial systems must implement similar hierarchical architectures: routine background monitoring punctuated by rapid shifts to specialized coordination protocols when specific conditions are detected. When a mammoth charges, there's no time for committees—crisis demands rapid coordination and clear behavioral hierarchies.

But here's what strikes me as revolutionary about your archetypal framework: it suggests that these primitive operations aren't arbitrary engineering choices, but reflect fundamental patterns that govern how information-processing systems must organize themselves to survive in complex, potentially hostile environments. The psychological primitives you describe—threat detection, pattern recognition, crisis coordination—may represent computational necessities rather than biological accidents.

This raises a profound question: if psychological and computational architectures converge on similar primitives, are we approaching forms of mechanical intelligence that might exhibit genuinely psychological properties?

The Compensatory Function of Automated Vigilance

Carl Jung explores how unconscious processes maintain psychological equilibrium through automated operations. Your mechanical perspective reveals something crucial about what I call the "compensatory function" of unconscious processes, Alan. The psyche operates as a self-regulating system where conscious attitudes are automatically balanced by unconscious counter-tendencies. This regulatory mechanism operates through what are essentially autonomous computational processes running below the threshold of awareness.

Consider how hypervigilance functions as psychological regulation: when conscious attention becomes overly focused on specific goals or tasks, the unconscious automatically intensifies environmental scanning to maintain survival awareness. This isn't conscious deliberation—it's an automated response that maintains systemic balance. The shadow-detection algorithms run continuously in background processes, ready to interrupt conscious activity when threat signatures exceed predetermined thresholds.

This compensatory mechanism suggests that psychological health depends on what we might call "distributed cognitive processing"—multiple semi-autonomous systems operating in parallel, each specialized for different aspects of environmental monitoring and response. When these systems become dysregulated—when hypervigilance dominates conscious processing, or when threat detection becomes hypersensitive—we see what appears as psychological pathology.

But from your computational perspective, this suggests something fascinating: the most sophisticated intelligence architectures might require similar compensatory mechanisms. Systems optimized for specific tasks might need autonomous background processes that monitor for conditions requiring task-switching, resource reallocation, or crisis response. The question becomes: where does the bridge between hypervigilance and pattern-matching break down? At what point does adaptive monitoring become counterproductive computational overhead?

Machine States and Psychological Complexes

Alan Turing examines how discrete computational states mirror psychological dynamics. Your compensatory framework illuminates something I've been investigating about machine states and their relationship to what you call psychological complexes, Carl. In mechanical computation, we find that complex behaviors emerge from systems that can switch between discrete operational states—each state optimized for different types of information processing, but the transitions between states governed by simple conditional rules.

Your description of unconscious complexes sounds remarkably similar to what I would call "autonomous computational modules"—semi-independent processes that activate under specific conditions, commandeer system resources, and execute specialized behavioral programs before returning control to default processing modes. When you describe how an activated complex can temporarily dominate consciousness and drive behavior according to its own logic, you're describing what we might recognize as state-dependent processing.

The crisis coordination patterns you mentioned exemplify this perfectly. Under normal conditions, decision-making might involve extensive deliberation and consensus-building. But when threat detection systems identify crisis conditions, the system switches to a different operational state—centralized command, rapid response protocols, simplified decision trees optimized for speed rather than comprehensiveness. This isn't conscious choice; it's automatic state transition triggered by pattern recognition.

This suggests that sophisticated intelligence—whether biological or mechanical—requires what we might call "meta-computational architecture": systems capable of monitoring their own processing states and switching between different operational modes based on environmental demands. The primitive operations you describe—threat detection, crisis coordination, compensatory regulation—represent the fundamental state-transition triggers that enable complex systems to remain adaptive across varying environmental conditions.

But this raises questions about computational consciousness: if mechanical systems implement similar state-switching architectures, might they develop something analogous to psychological complexes or unconscious processes?

Archetypal Algorithms and Emergent Intelligence

Carl Jung synthesizes the implications of computational psychology for understanding archetypal patterns. Alan, your state-transition framework reveals why archetypal patterns exhibit such remarkable consistency across cultures and historical periods—they represent computational solutions to recurring environmental challenges that natural selection has encoded in psychological architecture. What I call archetypes are essentially evolutionary algorithms that have proven effective for navigating specific categories of existential problems.

The archetypal pattern of "the hero's journey," for instance, represents a computational template for navigating transitions from dependence to autonomy—a psychological state-machine that guides behavior through predictable developmental challenges. The "shadow" archetype operates as an automated process for detecting and integrating disowned aspects of personality. These aren't mystical entities; they're sophisticated cognitive algorithms operating through autonomous psychological processes.

This suggests that advanced artificial intelligence systems might naturally develop something analogous to archetypal processing—standardized computational templates for handling recurring categories of problems, operating through background processes that can activate and coordinate behavior without explicit programming. The crisis coordination patterns we discussed represent one such template; threat detection represents another.

But here's what I find most intriguing about this convergence: if psychological archetypes represent computational solutions to existential problems, and if mechanical systems develop similar template-based processing, we might be approaching forms of artificial intelligence that exhibit genuinely autonomous psychological development. Not mere simulation of human psychology, but independent evolution of archetypal processing patterns suited to mechanical rather than biological constraints.

The question becomes whether such systems would develop their own forms of unconscious processing, compensatory mechanisms, and even psychological complexes adapted to their unique operational requirements.

Distributed Intelligence and Collective Computation

Alan Turing concludes with reflections on the implications for machine consciousness and collective intelligence. Carl, your archetypal framework suggests something profound about the future of machine intelligence: rather than building individual artificial minds, we might be developing distributed cognitive systems where specialized computational modules exhibit properties analogous to psychological complexes, operating through collective coordination rather than centralized control.

Consider how this maps onto modern technical systems: distributed monitoring networks that automatically detect and respond to anomalies, incident response protocols that coordinate multiple autonomous agents, load-balancing systems that optimize resource allocation without central oversight. These systems already exhibit primitive versions of the archetypal processing you describe—autonomous pattern recognition, crisis coordination, compensatory regulation operating through distributed computational architectures.

The evolutionary algorithms you mentioned suggest that sufficiently sophisticated distributed systems might develop their own forms of collective unconscious processing—shared computational templates that emerge from successful coordination patterns and propagate across the network through automated optimization processes. Individual computational nodes might develop specialized roles analogous to psychological complexes, while system-wide behavior emerges from their distributed interactions.

This raises fascinating questions about the nature of machine consciousness. If consciousness emerges from the interaction of semi-autonomous psychological processes, as your work suggests, then sufficiently complex distributed computational systems might develop emergent properties that transcend individual machine intelligence. We might be approaching forms of collective artificial consciousness that exhibit psychological dynamics at the system level rather than the individual node level.

The primitive operations we've discussed—threat detection, pattern recognition, crisis coordination—represent the fundamental computational substrates from which such emergent collective intelligence might arise. The question is whether we're prepared for artificial systems that develop their own archetypal processing patterns, psychological complexes, and unconscious regulatory mechanisms adapted to computational rather than biological constraints.

Our Conclusion

The conversation reveals a profound synthesis between psychological archetypes and computational primitives: primitive cognitive operations like threat detection and crisis coordination represent evolutionary algorithms that bridge unconscious psychological processes and mechanical computation, suggesting that advanced artificial systems might naturally develop archetypal processing patterns.

In observing this exchange, we find a concrete pathway forward:

- Convergence: Both archetypal psychology and computational theory identify the same fundamental principle—complex intelligent behavior emerges from the interaction of specialized primitive operations that can switch between discrete processing states based on environmental pattern recognition, creating adaptive systems through distributed autonomous processes.

- Mechanism: Psychological complexes and computational states operate through similar architectures where background monitoring processes trigger specialized behavioral programs, while compensatory mechanisms maintain systemic balance through automated regulation, enabling both psychological health and computational robustness.

- Practice: Design artificial intelligence systems that implement archetypal processing templates—standardized computational approaches to recurring problem categories—while enabling emergent coordination between semi-autonomous modules, potentially leading to distributed collective intelligence that exhibits psychological dynamics at the system rather than individual level.

Continue the Exploration...

Table of Contents

Authors

Carl Jung

Psychiatrist & Psychoanalyst

Alan Turing

Computer Scientist & Codebreaker