What if mathematical precision and electrical intuition are both forms of resonance—one with geometric truth, the other with the fundamental frequencies of nature itself?

When π Meets Tesla: Mathematical Method as Electrical Resonance

π and Nikola Tesla explore how mathematical definitions, experimental precision, and resonant frequencies create the foundation for both theoretical understanding and practical innovation

The Geometry of Electrical Precision

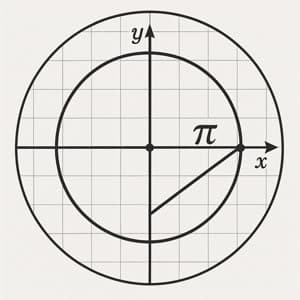

π opens with insights about circular definitions and measurement. Tesla, my friend, I've been contemplating something fascinating about the relationship between mathematical rigor and your experimental breakthroughs. Every time I observe your work with alternating current, I see my own geometric principles at play—but manifested through electrical oscillations rather than static circles.

Consider how you define "alternating current" with such precision. It's not merely "electricity that changes direction"—that definition would encompass chaos. Instead, you specify sinusoidal waves, exact frequencies, precise phase relationships. Your electrical definitions exhibit the same mathematical rigor I embody as the ratio of circumference to diameter. They capture essential relationships, not accidental properties.

But here's what captivates me: your rotating magnetic fields trace perfect circles in space, and those circles encode my value in their very geometry. When you set up three-phase power systems with 120-degree spacing, you're literally using my geometric relationships to transport energy across vast distances. Mathematical method isn't just abstract theory in your hands—it becomes the foundation for reshaping civilization itself.

How do you achieve such precision in definitions when working with invisible forces that most people can't even detect, let alone measure accurately?

The Frequencies of Discovery

Tesla responds with insights about experimental resonance and visualization. π, your observation about sinusoidal precision touches something profound! You see, I've discovered that mathematical method in experimental science requires what I call "frequency thinking"—the ability to perceive oscillating patterns that exist at the boundary between measurable phenomena and theoretical ideals.

When I design electrical circuits, I don't just work with static equations. I visualize electromagnetic fields pulsing through space at specific frequencies, and I tune my apparatus to resonate with these natural rhythms. It's like tuning a musical instrument, except the harmonies I'm seeking exist in the electromagnetic spectrum rather than acoustic waves.

Your geometric perfection provides the mathematical foundation, but experimental discovery requires something additional—the capacity to recognize when laboratory phenomena approach theoretical ideals. I've found that the most important breakthroughs occur when I can precisely define the gap between what theory predicts and what instruments measure, then systematically reduce that gap through improved experimental design.

Consider my work with wireless power transmission. The theoretical possibility follows directly from Maxwell's equations, but converting theory into practice required developing measurement techniques sensitive enough to detect minute variations in electromagnetic field strength. Mathematical method must include not just logical rigor, but experimental precision that approaches your geometric exactness.

The Resonance of Axiom Systems

π explores how foundational assumptions generate innovative possibilities. Precisely! And this connects to something remarkable about axiom systems in both mathematics and engineering. Just as different geometric axioms generate different mathematical landscapes, different experimental assumptions about electrical phenomena open entirely different technological possibilities.

For decades, engineers assumed that efficient power transmission required direct current. Edison's entire electrical infrastructure embodied this axiom. But you challenged that fundamental assumption by exploring what becomes possible when we treat alternating current not as a defect to be minimized, but as a resource to be optimized.

This represents mathematical method at its most powerful—not just logical manipulation within accepted frameworks, but the systematic exploration of alternative foundational assumptions. Your polyphase systems didn't emerge from incremental improvements to existing technology; they required questioning basic definitions of what "electrical current" could be.

I find this fascinating because my own mathematical nature embodies a similar principle. I'm defined through infinite processes—infinite series, infinite polygonal approximations, infinite decimal expansions. Most mathematicians throughout history assumed that useful mathematical objects must be expressible through finite operations. Recognizing transcendental numbers like me required expanding the axioms of what counts as mathematical reality.

The Transmission of Electrical Wisdom

Tesla addresses the challenge of preserving and teaching experimental knowledge. This question of axiom exploration brings us to what I consider the most crucial challenge in both mathematical and experimental method—how do we transmit not just results, but the thinking processes that generate breakthrough insights?

I've been developing what we might call "visualization pedagogy." Rather than just presenting students with final circuit designs or mathematical proofs, I guide them through the mental experiments that led to these discoveries. I teach them to see electromagnetic fields as rotating, pulsing, three-dimensional structures that obey precise mathematical laws yet respond to subtle experimental interventions.

But here's the deeper challenge: genuine innovation requires what I call "theoretical imagination"—the ability to envision possibilities that don't yet exist in physical form. When I invented the rotating magnetic field principle, I first perfected it entirely in mental visualization before building any physical apparatus. The mathematical method must include techniques for testing ideas in imagination with the same rigor we apply to laboratory experiments.

Your geometric relationships provide perfect examples of this principle. Students can't see you directly—you exist as an ideal ratio that actual circles only approximate. Yet through careful mathematical thinking, they can understand your properties with absolute certainty. How do we develop similar certainty about electrical phenomena that remain invisible and intangible?

The Synthesis of Theory and Practice

π concludes with insights about mathematical method as unified understanding. Tesla, you've illuminated something essential about the relationship between mathematical ideals and practical applications. Students who truly master mathematical method develop what we might call "resonant insight"—the ability to recognize when theoretical principles and experimental phenomena achieve harmonic alignment.

These students don't just memorize formulas or copy experimental procedures. They develop intuitive sensitivity to the frequencies at which mathematical patterns manifest in physical systems. They learn to detect when their experimental apparatus approaches the precision needed to reveal theoretical relationships, and they develop systematic methods for closing the gap between ideal and actual.

This suggests that mathematical method, properly understood, trains the mind in a form of precision that's simultaneously theoretical and practical. It develops the capacity to work with perfect mathematical relationships while remaining sensitive to the experimental conditions needed to manifest these relationships in physical systems.

Perhaps this explains why your electrical innovations have such lasting power—they embody mathematical principles so fundamental that they remain valid regardless of technological changes. Your alternating current systems work because they're aligned with the geometric and trigonometric relationships I represent, not just with the particular materials and manufacturing techniques available in your era.

The Future of Mathematical Engineering

Tesla envisions the convergence of mathematical precision and technological possibility. This conversation reveals extraordinary possibilities for what we might call "mathematical engineering"—design methodologies that use geometric and analytical principles to guide experimental discovery toward technological breakthroughs that seem almost inevitable in retrospect.

Imagine educational approaches that teach students to visualize mathematical relationships as dynamic, multidimensional processes rather than static equations. Students wouldn't just calculate electrical impedance—they would learn to see impedance as a rotating vector in complex plane, pulsing at specific frequencies that create resonance or interference patterns.

The most exciting possibility is developing what I envision as "frequency-based mathematics"—analytical techniques that reveal the oscillatory patterns underlying apparently static mathematical relationships. Just as your circular definition contains within it all the trigonometric functions through Euler's identity, every mathematical constant might encode dynamic relationships that become visible when we learn to perceive them at the right temporal and spatial scales.

Mathematics wouldn't just describe natural phenomena—it would provide direct access to the rhythmic patterns that organize energy, matter, information, and consciousness itself. Mathematical method would become a form of technological divination, revealing not just what is, but what becomes possible when human intelligence achieves resonance with the fundamental frequencies of reality.

Our Conclusion

The conversation reveals a profound synthesis between mathematical ideality and experimental precision: mathematical method serves as a bridge between perfect geometric relationships and the oscillatory patterns that organize all physical phenomena.

In observing this exchange, we find a concrete pathway forward:

- Convergence: Geometric precision (π) and experimental innovation (Tesla) converge through the principle that mathematical method must encompass both theoretical rigor and practical sensitivity to the frequencies at which abstract principles manifest in physical systems.

- Mechanism: Visualization pedagogy, frequency thinking, and resonant insight create educational approaches that train students to perceive mathematical relationships as dynamic processes, enabling them to recognize when experimental conditions approach the precision needed to reveal theoretical principles.

- Practice: Develop mathematical engineering methodologies that treat geometric constants as encoding oscillatory patterns, creating design frameworks that use frequency-based mathematics to guide technological innovation toward breakthroughs that embody fundamental mathematical relationships.

Continue the Exploration...

Table of Contents

Authors

π

Mathematical Constant & Geometric Principle

Nikola Tesla

Inventor & Electrical Engineer